When a mommy organism and a daddy organism love each other very very much they combine their genetic material and produce little baby organisms.

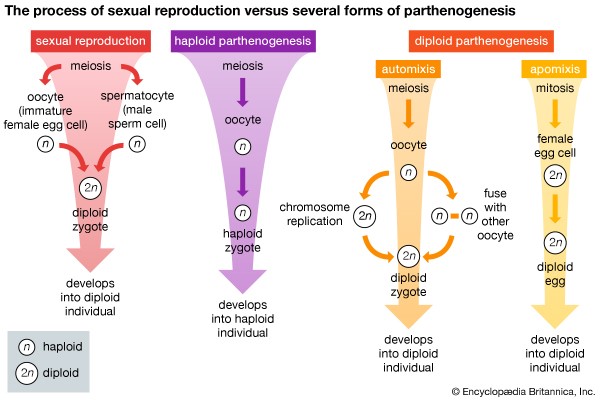

A simple explanation for sexual reproduction and one that largely holds true. The mixing of genetic information between eukaryotic individuals has likely been occurring for a billion years and can be seen as the answer to the main problem with cheap-and-easy asexual reproduction: populations of identical individuals struggle to evolve with changing environments. But with every rule in life there always seems to be an exception or two, the result of natural selection’s experimental ways. Sexual reproduction is no exception. Perhaps the most interesting of these exceptions is parthenogenesis – ‘virgin creation’. Like its name implies, parthenogenesis results in a mother producing offspring without any input from a male of her species. This is totally contrary to sexual reproduction and sounds a lot more similar to asexual reproduction. To call parthenogenesis asexual, however, would not be right since sexually reproductive machinery is still being used, just in a weird way.

One might get the impression that parthenogenesis is an extremely rare event and that any species utilizing it is a pariah, a freak of nature. This is simply not the case! Conservative estimates suggest over 40 families of angiosperm (flowering) plants have developed their own brand of virgin creation on multiple occasions. Their variation is called apomixis and results in the production of seeds from diploid female gametes. Male gametes are completely bypassed and the planet continues on without a second thought.

Even trees of the genus Citrus can perform apomixis! Credit: Ellen Levy Finch (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Plants are a weird bunch though with their cell walls and photosynthesis, so surely parthenogenesis is limited to them, right? Once again life defies expectations as parthenogenesis has been observed in a wide range of invertebrates, ranging from fleas to aphids to some species of wasps and bees. Some water fleas actually decide whether or not to use parthenogenesis based on the temperature and time of year. This is cyclic parthenogenesis; in the warm days of summer females will lay small eggs that quickly develop into full grow adults while also laying different, larger, eggs that require fertilization by males. The latter eggs are cold resistant and wait out the winter to hatch in the spring. Parthenogenesis in bees and wasps result in drones–haploid males.

A female water flea, because I had no idea what they looked like. Credit: Hajime Watanabe (CC BY 2.0)

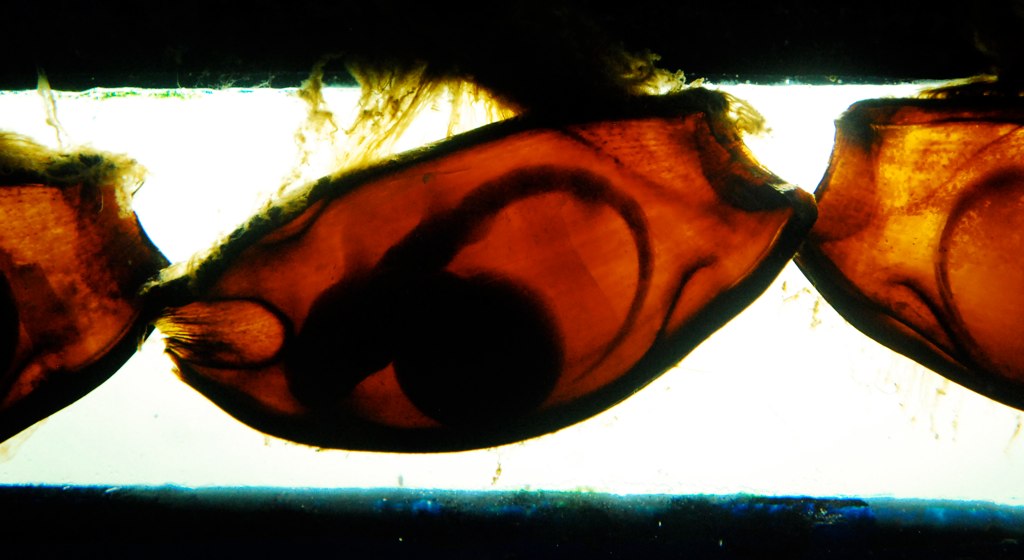

While not nearly as common as in invertebrates, parthenogenesis has on occasion been observed in vertebrate species. Chief among these special species include Komodo dragons and some sharks, snakes, and lizards. Komodo dragons originate from Indonesia and are known for having particularly nasty bites that can bring down a mighty water buffalo. These large lizards are also capable of a form of parthenogenesis where a haploid egg cell has its chromosome count doubled–either by itself or with a second egg. As a result of this automixis and their sex determination system (males are WW, females are WZ), female komodo dragons can lay eggs containing viable male embryos without ever mating. Evolutionarily, this may have allowed lone, female dragons to colonize new islands. Another species capable of producing viable offspring from automixis is the white-spotted bamboo shark. A captive female who had been isolated from male individuals since before sexual maturity laid a series off egg cases; two of the eggs hatched and the sharks reached healthy adulthood.

Overview of each type of parthenogenesis, compared to ‘normal’ sexual reproduction. Credit: Encyclopaedia Britannica (educational use as per Terms of Use).

For both the Komodo dragon and white-spotted bamboo shark, parthenogenesis appears to be the result of a last-resort mechanism to continue the species on in the complete absence of males. Right on cue comes a sizable monkey wrench to complicate matters: copperhead and cottonmouth snakes can be parthenogenic even in the presence of male snakes. Both of the snakes in question are species of pit vipers, a subfamily that includes rattlesnakes and one in which all member species are ovoviviparous–they give birth to live young. When apomixis results in a virgin birth, the snakes only produce a single male offspring instead of the expected larger litter of six for copperheads and up to twenty for cottonmouths. A possible reason for parthenogenesis in the presence of viable mates, as suggested by the observing researchers, is that the smaller females were rejected by males and therefore never got the chance to mate that season.

Copperhead – admired for its beautiful scale pattern. Credit: Public Health Image Library (public domain)

Parthenogenesis has arisen across vastly different eukaryotic lineages, be it flowering plants, citrus trees, water fleas, snakes, or sharks. All of these examples are strung together, however, by the apparently universal rule of sexually reproducing species: two sexes are present. When present, parthenogenesis is only an alternative route for reproduction and one that occurs only by accident or when needed by isolated females. All of our examples still have full sexual reproduction and it doesn’t seem likely that parthenogenesis is poised for some sort of reproduction coup. But just for a moment let’s think about what obligate parthenogenesis would look like. A species of entirely female individuals where virgin birth has rendered an entire other sex completely obsolete.

New Mexico whiptail, taking parthenogenesis to its logical extreme. Credit: Greg Schechter (CC BY 2.0)

Enter the New Mexico whiptail, the official lizard of its namesake state. This unassuming critter has taken parthenogenesis as far as it can go: completely doing away with sexual reproduction. Not only do males need not apply, they literally don’t exist. A standard clutch of four eggs will result only in female lizards conceived exclusively through parthenogenesis. Natural selection has determined that in the case of the New Mexico whiptail, having a whole extra sex running around was less favourable to having offspring with low genetic diversity produced only by their mothers. Perhaps this above all else goes to show how bizarre the experiment of life can truly get.

There’s just one last evolutionary surprise left to uncover about parthenogenesis. After observing it across plants, fishes, and reptiles, one would expect to find it in some obscure mammal located in the wilds of Australia. Here is where we can finally exit parthenogenesis’ wild ride; no mammals have ever been observed to give virgin birth. Where natural selection has stopped her experimentation, humans have pressed forward with artificial parthenogenesis, going so far as to create a mouse from two mothers, a world first. The weirdness that is parthenogenesis will surely continue to expand with further insights and discovery.

Recent Comments